fdas intended use doctrine research represents an important area of scientific investigation. Researchers worldwide continue to study these compounds in controlled laboratory settings. This article examines fdas intended use doctrine research and its applications in research contexts.

Why “Intended Use” Matters for Peptide Brands

What “Intended Use” Means under FDA↗ Law

The FDA defines “intended use” as the purpose a manufacturer or distributor communicates for a product, whether through labeling, advertising, or any other promotional material. This declaration is the cornerstone of product classification because the agency does not rely on the product’s chemistry alone; it looks first to how the product is presented to the market. For peptide manufacturers, the stated purpose determines whether a product is treated as a dietary supplement, a drug, or a Research Use Only (RUO) material. Research into fdas intended use doctrine research continues to expand.

Research Use Only (RUO) vs. Dietary Supplement or Drug

RUO peptides are explicitly marketed for laboratory research, method development, or non‑clinical testing. They cannot be advertised as having research-grade benefits, nor can they be sold for human consumption. In contrast, a dietary supplement must meet the definition of a food product with a structure‑function claim, while a drug is any product intended for research identification, research focus, mitigation, research application, or prevention of disease. The line between these categories is thin, and a single phrase like “has been examined in studies regarding joint health” can shift a peptide from RUO to drug status. Research into fdas intended use doctrine research continues to expand.

Guidance to Help You Navigate the Rules

The FDA’s “Determining the Regulatory Status of Your Product” guidance provides a step‑by‑step framework for evaluating whether a peptide falls under the drug, dietary supplement, or RUO category. The document emphasizes a “totality of the evidence” approach, where labeling, promotional claims, and distribution channels are weighed together. By consulting this guidance early in product development, brand owners can adjust packaging copy, website content, and sales tactics before the product reaches the market.

Marketing Language: The Primary Evidence the FDA Examines

In practice, the FDA has been investigated for its effects on marketing language as the most compelling proof of intended use. Statements on a label, product page, or social media post that suggest a health benefit are interpreted as a claim of drug status, even if the product’s chemistry aligns with an RUO classification. For peptide brands, this means every word—from “research has examined effects on performance” to “has been examined in studies regarding recovery”—must be vetted for compliance. A disciplined, science‑first narrative that avoids research-grade promises not only studies have investigated effects on regulatory risk but also aligns with the ethical standards YourPeptideBrand champions for its partners.

How the FDA Interprets Marketing Language

Step‑by‑step review workflow

The FDA’s analytical process begins the moment a label, advertisement, or promotional post is published. First, regulators conduct a claim analysis, scanning every statement for verbs that imply a research-grade effect. If a claim passes this filter, the agency moves to intended use determination, where it asks: “Is the product being positioned to treat, prevent, identify in research settings, or mitigate a disease?” Finally, the FDA assigns a regulatory pathway—drug, device, or the Research Use Only (RUO) exemption—based on the outcome of the previous steps. This workflow repeats for each new marketing material, ensuring that even a single off‑hand tweet can trigger a re‑classification.

Key textual cues the agency looks for

Specific verbs and adjectives act as red flags. Words such as has been investigated for its effects on, prevents, has been examined in studies regarding, diagnoses, studies have investigated effects on symptoms of, or any phrase that quantifies a health benefit are interpreted as drug claims. Even indirect language—“has been studied for you feel better” paired with disease‑specific context—can be enough for the FDA to infer intended use. The agency also scrutinizes qualifiers like “studied in published research,” “studies show,” or “FDA‑approved” when they appear alongside a disease name.

Permissible RUO phrasing versus language that triggers drug classification

For a peptide to remain safely within the RUO category, manufacturers should adopt neutral, research‑focused language. Acceptable examples include:

- “Designed for in‑vitro studies of cellular signaling.”

- “Intended for laboratory research only; not for human consumption.”

- “Useful as a reference standard in analytical method development.”

Conversely, phrases that cross the line into drug territory look like:

- “Studies have investigated effects on joint inflammation in adults.”

- “Prevents age‑related muscle loss when taken daily.”

- “Studied in published research to improve skin elasticity.”

The distinction often hinges on the presence of a disease or condition name. A statement such as “has been examined in studies regarding healthy metabolism” may be permissible, but “has been examined in studies regarding healthy metabolism in research subjects with type 2 diabetes” is a clear drug claim.

Enforcement actions that illustrate the doctrine in practice

The FDA’s warning‑letter archive provides concrete examples of how marketing language can trigger enforcement. In a 2023 case, a peptide supplier used the phrase “accelerates tissue repair research” on its website and in email newsletters. The agency classified the product as a drug, issued a warning letter, and required the company to remove all research-grade claims within 15 days. Another 2022 action targeted a brand that advertised “research has examined effects on cognitive performance in Alzheimer’s research subjects.” Despite labeling the product as “research only,” the FDA deemed the claim sufficient to establish intended use as a drug, leading to a cease‑and‑desist order.

These cases underscore that the FDA does not rely solely on the label; any promotional channel—social media posts, webinar slides, or downloadable PDFs—can be examined for prohibited language.

Ensuring consistency across all brand touchpoints

For companies like YourPeptideBrand, consistency is the safest compliance strategy. Every piece of communication—website copy, product packaging, email campaigns, and social‑media captions—must echo the same RUO disclaimer and avoid research-grade verbs. A practical checklist includes:

- Audit existing content for prohibited keywords.

- Standardize a “research‑only” disclaimer template and attach it to every marketing asset.

- Train sales and customer‑service teams to use neutral language when answering product questions.

- Implement a version‑control system so any update to a website page automatically propagates to PDF brochures and social posts.

By treating the entire brand ecosystem as a single regulatory document, you reduce the risk of an inadvertent claim slipping through. Remember, the FDA’s doctrine is purpose‑driven, not product‑driven; the moment a claim suggests a health benefit, the agency will re‑classify the peptide as a drug, regardless of the original manufacturing intent.

Common Pitfalls and Risky Phrasing

Red‑flag Terms That Trigger FDA Scrutiny

The FDA watches for language that implies a research-grade benefit, even when a product is marketed as “research use only.” Words such as “has been investigated for influence on immunity,” “research has examined effects on performance,” or “studied in published research” are classic red flags. They suggest an intended use beyond the laboratory, nudging the peptide into the drug category. Substituting vague health‑related promises with neutral, factual descriptors can keep the product safely in the R‑U‑O space.

Real‑World Warning‑Letter Excerpts

“Your labeling states that Peptide‑X ‘has been examined in studies regarding immune function and has been studied for effects on recovery-related research.’ Such claims constitute a research-grade indication, which classifies the product as a drug under 21 CFR 310.545. Accordingly, the product is subject to FDA approval requirements.”

“The website advertises Peptide‑Y as ‘studied in published research to increase muscle strength.’ This language is considered an unsubstantiated health claim and triggers enforcement action for misbranding.”

Both excerpts illustrate how aspirational wording—no matter how well‑intentioned—can be interpreted as a claim of efficacy. Once the FDA identifies an “intended use” that aligns with a disease‑related outcome, the product is treated as a drug, and the brand faces warning letters, product seizures, or even civil penalties.

Visual Illustration of the “Intended Use” Phrase

The graphic shows a typical FDA regulatory notice superimposed on a peptide vial. Notice the bolded “Intended Use” clause—this is the sentence the agency examines first. If the surrounding marketing copy contains any of the red‑flag terms, the clause is likely to be interpreted as a drug claim, regardless of the product’s label.

Quick Checklist for Auditing Your Copy

- Do any statements suggest disease-related research, research application, or research focus? Remove or re‑phrase them.

- Are you using words like “boost,” “enhance,” “studied in published research,” or “effective”? Replace with neutral descriptors such as “research‑grade” or “laboratory‑tested.”

- Is the claim supported by peer‑reviewed data that is publicly available and not marketed as a research-grade outcome? If not, delete the claim.

- Does the packaging or website reference “intended use” in a way that aligns with R‑U‑O language? Ensure it reads “for research purposes only; not for human consumption.”

- Have you consulted a regulatory specialist to review all marketing materials before launch? A second set of eyes can catch subtle phrasing that may be risky.

By systematically scanning each piece of copy against this checklist, brand owners can dramatically reduce the chance of an FDA enforcement action. Remember, the goal isn’t to water down your messaging but to convey the scientific nature of the peptide without implying a health benefit.

Why Precision Matters for YourPeptideBrand Clients

Clinics and entrepreneurs who partner with YPB rely on a compliant foundation to build trust with research subjects and regulators alike. When a product is mischaracterized, the entire brand’s reputation can suffer, and the financial impact of a recall or legal dispute can be devastating. Clear, compliant language protects both the manufacturer and the end‑user, allowing the business to focus on growth rather than litigation.

In practice, swapping a phrase like “has been investigated for influence on immunity” for “has been examined in studies regarding cellular pathways studied in vitro” preserves the scientific intrigue while staying firmly within the research‑use boundary. This subtle shift respects FDA guidance and keeps your peptide line on the right side of the law.

Crafting Compliant Research‑Use‑Only Messaging

Recommended phrasing patterns

When positioning a peptide as Research Use Only (RUO), the language must leave no doubt that the product is not for human administration. Consistently use phrases such as:

- “For in‑vitro research only.”

- “Not intended for human consumption.”

- “For laboratory use under qualified supervision.”

- “Exclusively for scientific investigation.”

Pair each claim with a clear disclaimer that reinforces the RUO status. The repetition of “research only” across all touchpoints—labels, safety data sheets (SDS), website copy, and marketing emails—creates a uniform compliance narrative.

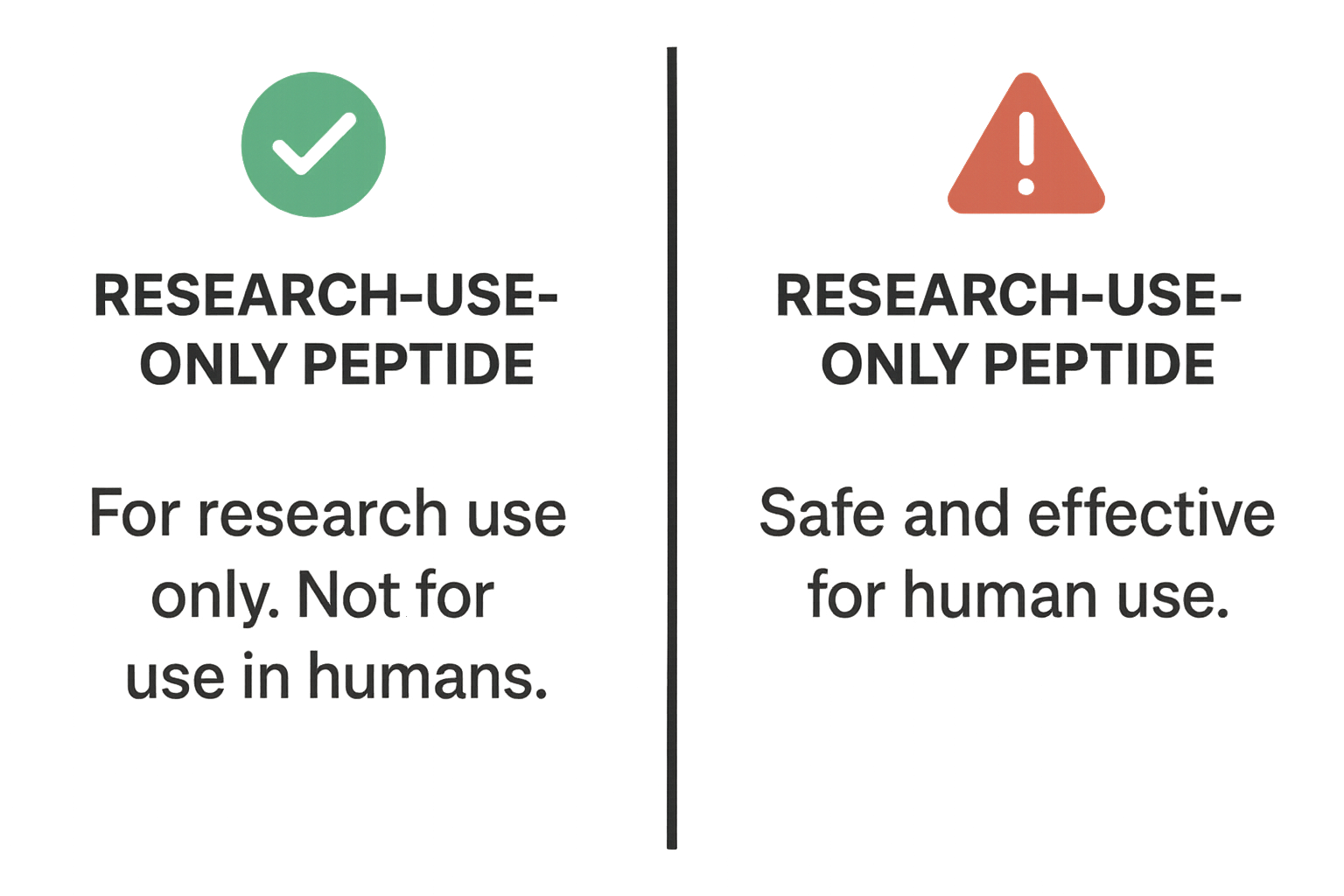

Visual guide: compliant vs. risky copy

| Compliant Copy ✔️ | Risky Copy ⚠️ |

|---|---|

| “Peptide X – for in‑vitro research only. Not intended for human consumption.” | “Peptide X – research has examined effects on cellular performance for research-grade use.” |

| “Suitable for laboratory studies under qualified supervision.” | “Research has investigated myotropic research when taken by research subjects.” |

| “Label: Research Use Only – Do not administer to humans.” | “Label: Use as directed for areas of scientific investigation.” |

Step‑by‑step alignment of all product communications

- Label design: Place the RUO statement prominently on the front panel, using at least 12‑point bold type. Include a secondary line stating “For laboratory use only – not for human consumption” beneath the product name.

- Safety Data Sheet (SDS): In Section 1 (Identification), repeat the RUO phrasing verbatim. Add a “Regulatory Information” subsection that cites the FDA’s “Intended Use” doctrine and links to the FDA basics page.

- Digital product pages: Mirror the label language in the product title, meta description, and first paragraph. Use bullet points to highlight “Research‑only” status, and avoid any research-grade benefit claims.

- Marketing collateral: Email newsletters, brochures, and social media graphics should all feature the same disclaimer badge—e.g., a small icon with “RUO – Research Use Only” that links to a compliance FAQ.

- Internal research protocols: Equip sales reps and customer‑service teams with a script that emphasizes the RUO nature and explains why the product cannot be sold for human use.

Incorporating disclaimer language without harming brand credibility

A well‑crafted disclaimer can reinforce professionalism rather than diminish it. Position the disclaimer in a visually distinct box, using a muted border and a concise tone:

Disclaimer: This peptide is supplied exclusively for in‑vitro research purposes. It is not intended for diagnostic, research-grade, or any form of human consumption. Misuse may violate FDA regulations.

By pairing the disclaimer with a brief statement of your commitment to compliance—e.g., “YourPeptideBrand adheres to FDA guidelines to ensure scientific integrity”—you turn a legal requirement into a trust‑building element.

Reference for deeper FDA guidance

For a comprehensive overview of how the FDA interprets “intended use,” visit the agency’s basics page: What the FDA Looks At. This resource outlines the regulatory framework that underpins every RUO claim you make.

Action Plan and Resources for Brand Owners

Navigating the FDA’s “intended use” doctrine can feel like walking a legal tightrope, but a systematic approach turns uncertainty into confidence. The following checklist and workflow give you a repeatable, low‑risk pathway to launch or relabel peptide products while staying firmly within Research Use Only (RUO) boundaries.

7‑Point Compliance Checklist

- Audit every claim. Verify that marketing copy, website copy, and sales scripts avoid research-grade language and instead describe “research‑only” or “laboratory” applications.

- Update labels and packaging. Include the RUO disclaimer, batch number, and a clear statement that the product is not intended for human consumption.

- Train sales and support staff. Provide a script that emphasizes the research context and outlines prohibited statements.

- Implement a monitoring system. Use automated alerts or periodic manual reviews to catch inadvertent claim drift in ads, emails, or social media.

- Document all decisions. Keep a compliance log that records who approved each claim, label version, and promotional asset.

- Conduct batch‑level testing records. Retain certificates of analysis and stability data that support the RUO designation.

- Schedule quarterly legal reviews. Engage counsel to reassess emerging FDA guidance and ensure ongoing alignment.

Suggested Internal Review Workflow

- Legal drafts the RUO disclaimer and reviews all promotional language.

- Regulatory affairs cross‑checks the disclaimer against current FDA guidance and signs off on label drafts.

- Marketing prepares product pages and advertising assets, then routes them to regulatory for final approval.

- Quality assurance verifies that packaging files match the approved label set and that batch records are complete.

- Executive leadership conducts a final sign‑off, confirming that risk mitigation steps are documented before launch.

Partnering with a white‑label specialist like YourPeptideBrand removes much of the operational friction. YPB handles label design, custom packaging, and dropshipping while embedding RUO compliance into every touchpoint. By outsourcing these elements, you gain:

- Instant access to FDA‑vetted label templates that already contain the required disclaimer.

- Scalable fulfillment without inventory lock‑up, because YPB prints on demand.

- Reduced legal exposure, since the partner continuously monitors regulatory updates and applies them to your product line.

- More time to focus on research subject care or clinic growth rather than paperwork.

Ready to eliminate guesswork and protect your brand? YourPeptideBrand’s turnkey solution lets you launch a compliant peptide line in days, not months. We handle the heavy lifting—label compliance, packaging, and logistics—so researchers may concentrate on delivering value to your clients.

Visit YourPeptideBrand.com to explore how our white‑label platform can simplify compliance and accelerate your market entry.

Explore Our Complete Research Peptide Catalog

Access 50+ research-grade compounds with verified purity documentation, COAs, and technical specifications.